While in remote residence with Jenni House, I gave a virtual artist talk about my process and what has led me to access-centered making. This recording is shortened and includes an ASL interpreter on screen and subtitles available to turn on.

Read MoreIceland. Mobility, Spatiality, Virtuality. /

Iceland. Mobility, spatiality, virtuality. Defining new touristic relationships through remote encounters, distant desires and embodied experiences.

A one day symposium hosted by (Arts) Territory Exchange, Strondin Studio Seyðisfjörður, and Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University >>> Morag Patterson and I (partnered artists in an ongoing residency through correspondence) presented on our personal and overlapping experience with Iceland; the only place our physical paths have crossed. Below is the recording of the symposium, our’s is in the last session video, starting at minute 20:55.

www.artsterritoryexchange.com/iceland-mobility-spatiality-virtuality-conference-recordings

Transcript of my presentation.

Iceland and Alaska share many similarities: latitude, climate, weather, vegetation, birdsong, volcanic fire, sweeping ice, boom or bust, industrial tourism, overfishing, hydroelectric “green” energy, and both have been colonized, and both “sell” place through a language of empire; marketing land as a resource, a myth of exploration and escape, a frontier to discover; an untouched, pristine, wild, raw, extreme, rugged, unspoiled, unclaimed, unnamed, unmanned, remote place to fulfill your dreams and fantasies. Both claim the Arctic for geopolitical power, both are claimed by a rapidly warming latitude; both exist in the paradox of selling off ‘resources’ to meet economic demands while claiming clean, unmatched ‘nature’ of ‘last chance’ tourism while remaining heavily dependent on imported food and supplies while exploring ‘natural resources.’ Both have been defined as ‘other’ where people from outside define place for other outsiders to experience ‘exotic’ nature. Both have relatively short western histories and are indifferent to personal comfort; dynamic places that remind us of our vulnerability.

Sitka spruce, lodgepole pine, black cottonwood, Nootka lupine – all species imported to Iceland from Alaska. The lupine, to help with erosion, now runs rampant throughout many parts of the country, with showy carpets of purple that suffocate local plants, and for some, offer pleasing views. Reforesting the island is proving much slower than the spread of lupine. These trees, imported from Southeast Alaska, from a town just up the fjord from my home, were gathered as seeds in the 1940s and 50s. With slow growth rate, any changes in the Icelandic landscape itself are negligible; Alaska’s influence showing up more as tourists on direct flights from Anchorage than large swaths of forest. These shifts in plant communities, attempts to stabilize barren, wind-swept, volcanic laden soils, parallel my personal story of visiting Iceland: I went to grieve the shifting north and ended up also mourning the shaky ground of my own existence.

In a sense, the flora transported to Iceland from Alaska mirrors my reflection on that time and mirrors the dialog between myself and Morag as we learn from each other’s experience and decisions through place. We’ve both come to recognize that knowing a place exists far outweighs having to experience it or exist within it.

I went to escape, to exist in a place unknown, to see if what was happening to my home was true, that our warming North was circumpolar, and ask myself how and where my art and story fit in the narrative of such drastic human-caused change. A majority of the photos I have of myself from that time are of reflections and distortions in glass and mirrors, shadows and silhouettes, like I didn’t really exist there at all, nor leave a trace of recognizing myself there. I look back on my time in Iceland and feel like I existed only in fragments, like a phantom, and when I look through the images of the land, they feel like a haunting, like I’ve seen it before but where. Can we exist anywhere fully if we’ve come from somewhere else?

Looking through my photographs of the land, I see the blurred lines that shape the north, that my home in Alaska faces a future similar to Iceland’s, a future where mythical borders and boundaries are obsolete, that what effects the North affects us all.

References:

Egill Bjarnason. 2018. “Why Iceland Is Turning Purple: Buoyed by climate change, an invasive plant is taking over the landscape of the island nation.” Hakai Magazine. https://www.hakaimagazine.com/features/why-iceland-is-turning-purple/

Kristín Loftsdóttir. 2015. “The Exotic North: Gender, Nation Branding and Post- colonialism in Iceland”. NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 23(4), bls. 246-260. DOI: 10.1080/08038740.2015.1086814

Kristy Kay Griffin and Caitlin Rogers. 2017. “Fabricating the Alaskan Frontier”. Juneau Empire. https://www.juneauempire.com/life/fabricating-the-alaskan-frontier/

A Stitch in Time /

Photo credit: Today Art Museum

Through Arts Territory Exchange, two photographs are included in “A Stitch in Time” exhibition at the Today Art Museum in Beijing, China. Curated by the art critic Huang Du & art historian Jonathan Harris, in partnership with Gurdun Filipska of Arts Territory Exchange.

Craney says: "Alaska has a new language--this summer's excessive heat, drought, fire, and melt has forced us to redefine the accumulation zone as the ablation zone, or melt zone. These fragments of the physical landscape now only exist in our memory; what was has washed to the sea. Living with this drastic landscape change is heartbreaking, real, and happening fast. We all need to do our part to save the places and people that make up our homes…In her final book Becoming Earth, Eva Saulitis wrote, “It takes many ways of knowing to overcome the brain’s many refusals.” My work circles around physicality of materials and endless questioning: What brings us together when the world falls apart around us? How do we keep up with the onslaught of tragedy, extinction, and grievance? Where do we find community when the ground underneath us falls away, taking with it our cultures, food, and stories? Grief requires us to know the time we’re in, therefore, grief ends up not being about hope, rather humility and dignity.’’

“Where the edge of the Alaskan cryosphere has let go”

You Are A Tender History Of Ice /

Published with images in Minding Nature: Spring 2019, Volume 12, Number 2, alongside If Your House Is on Fire: Kathleen Dean Moore on the Moral Urgency of Climate Change, by Mary DeMocker

Deciphering Change in the Alaskan Landscape /

Grief Dares Us © Katie Ione Craney 2017

Abstract

The Alaskan landscape challenges those who try to depict the experience of place through visual language. How artists decipher the complex intricacies of a changing climate in an already dynamic landscape is vital to understanding past and future concepts of change in Alaska. Daily patterns and cycles are becoming more unpredictable, making it difficult to visualize, measure, and adapt to new ways of living on and with the land. How artists see, comprehend, deconstruct, and communicate these complicated narratives aides in understanding the stress of human-caused climate change on the northern landscape.

Please cite this chapter as:

Craney K.I. (2019) Deciphering Change in the Alaskan Landscape. In: Palocz-Andresen M., Szalay D., Gosztom A., Sípos L., Taligás T. (eds) International Climate Protection. Springer, Cham

Observing Alaska's Changing Climate Through the Eyes of an Artist /

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change interview on my practice, research, and work.

This article is a part of the series #Art4Climate, a joint initiative by the UNFCCC secretariat and Julie’s Bicycle on the work of artists who make the issue of climate change more accessible and understandable by featuring it in their work. It was inspired by a session at the Salzburg Global Seminar in early 2017.

“There is a paradox to living in the north. Much of Alaska’s economy, historic to present, is based on extraction: the fur trade, mining, forestry, fisheries, and most significantly, the discovery and reliance on oil and gas. Hands down, this land is full of valuable resources,” she says.

“Many look at this land and see only dollar signs, while others see vast wilderness, vibrant cultures, and complete, complex ecosystems. The north is experiencing rapid climatic changes. In Alaska, we hear the news on our local public radio station and see images from across the state; we see change happening right outside our front door.”

We Hardly Know Our Own /

The Alaskan landscape surrounding my home plays an essential role in my work. I rely on the land for its tangible qualities and pay close attention to its nuances. Through the art making process, I can take a landscape and break it down like an ecologist would, looking at different layers, stories, and interconnections that create the specific place.

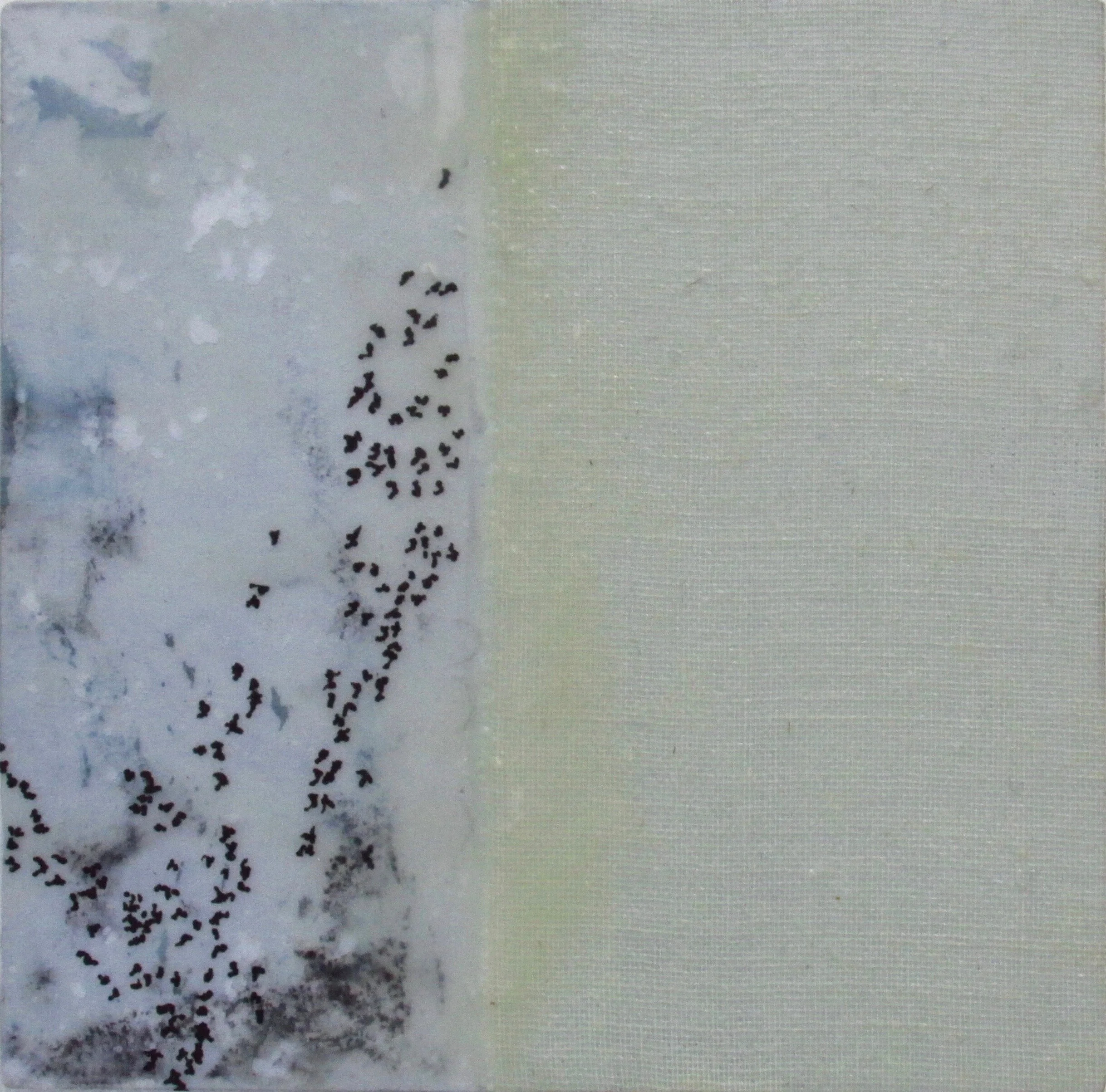

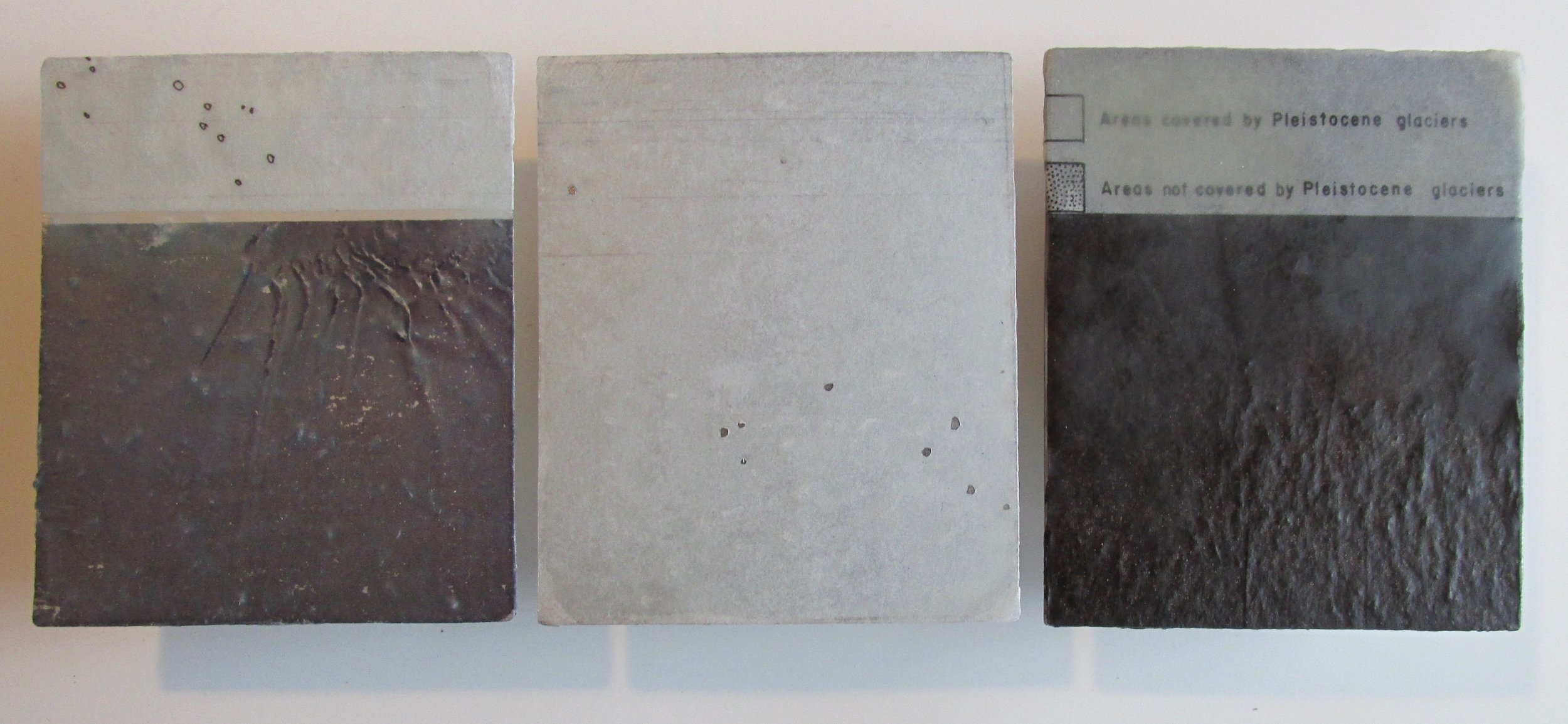

We Hardly Know Our Own - Photo transfer, ink, tissue, paper, and encaustic on hand-cut scrap metal

Left Coast Annual Juror's Merit Award, Sanchez Art Center, Pacifica, CA. Juror Susan Sayre Batton, Interim Director of the San Jose Museum of Art

In We Hardly Know Our Own, the imagery and materials unfolded chronologically, to tell one small piece, and my interpretation of, a new geologic epoch. The land is still coming out of a geologically recent ice age; evidence is everywhere. In the maritime climate of Southeast Alaska, water – both liquid and solid – has forced its way – with the help of gravity – to shape bedrock, tear down mountainsides, and carve deep fjords. Earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, and glacial advance, retreat and rebound have all shown that the earth is very much alive and continues to be reborn. Many of these events go untamed, unmanaged, and unnoticed by most humans since Alaska is so large that many events happen without significant threat to human population centers. How do we know, relate, and narrate the complexities of geologic time while witnessing a new geologic era, the age of man, the Anthropocene?

Telling the story of the place I live, the challenges Alaska faces, and the outcomes ahead, is only a tiny thread in the larger weave told through art, visual communication, and discourse. My work is a reflection on loss, memory, rebound, and change, as well as a window into this particular place. Daily patterns and cycles are becoming more unpredictable, making it difficult to visualize, measure, and adapt to new ways of living on and with the land. How we see, comprehend, deconstruct, and communicate these complicated narratives aides in understanding the stress of human-caused climate change on the northern landscape.

Deciphering Change: An Interview with Katie Ione Craney /

Check out a recent interview with artArctica, a Finland-based artist group who explores the role artists have in understanding the complexities of the Arctic.

The Air We Breathe - Artists and Climate Change /

What roles do phytoplankton and ocean acidification play in our everyday life? Living in Southeast Alaska, clean water and salmon are an irreplaceable staple in our livelihood. As I began researching the importance of salmon, it became apparent that plankton and clean water hold the key to our entire ecosystem. Check out my findings, written for Artists and Climate Change.